Part 1: The Decalogue

And the Lord spoke to you from the midst of the

fire. The sound of words you did hear but no image did you see

except the sound. And He told you His covenant that He charged you

to do, the Ten Words, and He wrote them on two tablets of stone.

Deuteronomy 4:12-13

The Ten Commandments are

probably the most famous bit of legislation in the world. Modern

scholars are not sure, however, where exactly the Ten Commandments

are, nor what they really mean.[1]

God as an Author to be Imitated

This book is about the Torah as a composition,

with special focus on its structure. It presents the discovery that

all five books are made up of well-defined literary units that share

certain characteristics. Specifically, each unit was built as a

table or weave, a two-dimensional, non-linear construct. This

discovery made it possible to identify all the individual literary

units of the Torah. They produce a very clear picture of the formal

structure of each of the five books. Since the same formatting

technique was used throughout the Torah, both on the level of

individual literary units and on the level of whole books, it was

apparently constructed by a single hand or school, which I refer to

as the “author”. The discovery of the literary format of the Torah

and its parts makes it possible to read the Torah in a new way, as a

multi-leveled, highly sophisticated composition. The new reading is

guided by the structure as well as certain elements of the narrative

which can be understood as reading instructions. The Torah can thus

be read in two distinctly different ways, one traditional and the

other new. The traditional way does not take into account the

structure, while new way does. Through the course of this book I

demonstrate that the author intended that the Torah be read in both

ways. The foundation text for the double reading is the Decalogue,

which can also be read in two ways.

The Torah presents the Decalogue as God’s only

handwritten literary work. It thereby indicates that the Decalogue

should be seen as the most exalted possible work of literature, a

literally divine text. There are further signs of its importance. We

are told that the Decalogue, as opposed to the rest of the Torah,

was written by the hand of God on stone tablets which were placed in

the Ark of Testimony. This put them at the focus of the Israelite

camp. The tribes were arrayed around the Tabernacle. The tablets

containing the Decalogue written by God’s hand were in the Ark

within the Holy of Holies, at the focus of the camp. The tablets

within the Ark also enabled God to communicate with Moses from

between the cherubim decorating the Ark. It is hard to image how an

author could note the importance of a text more emphatically. I want

to suggest that this unique status also provides the careful reader

with information concerning how the Torah was composed. Since the

Decalogue is the exemplar of the highest possible form of writing,

it follows that it is the one most worthy of imitation.

Consequently, one could expect that the rest of the Torah is

influenced by the Decalogue as a work of literature. There is

evidence that the composition of the Torah parallels the Decalogue

in two ways: in the literary format of the text and in the audience

it addresses. We will first look at the audience, and then at the

content.

God inscribed two sets of stone tablets for two

different recipients. One set, the first, was intended for the whole

nation to see. The second set was intended for Moses’ eyes alone.

Moses brings the first tablets into the camp and shatters them

“before your eyes (Deut. 9:17).” This shows that they were created

by the hand of God to be presented to the whole people. It is

shocking that God shows no concern when Moses destroys the work of

His hands. This lack of response seems to indicate that Moses’ act

was appropriate. The tablets created for the whole nation to see,

should, or could, only be seen in pieces. The second set was very

different. God told Moses to prepare a container for them, before He

engraved them with exactly the same words that were on the first

tablets. After they were engraved, Moses was to place them directly

in the container. None but Moses was to see them. By connecting the

two separate narratives we learn that God inscribed exactly the same

text twice, each time for a different audience. The public text, the

first tablets, was shattered. The private text, the second tablets,

remained coherent, whole.

If the Torah is in fact modeled according to

the pattern of the Decalogue, we now have some information about it

should be read. It can be read in a public way as a shattered text,

or in a private way which views the text as a whole. There is still

more information to be derived from the precise language used to

describe the formation of the two sets of tablets. Regarding the

first tablets we are told: הלחת מעשה אלהים

“the tablets were of God’s making (Exod 32:16).” God tells

Moses to make the second tablets in these words

פסל לך שני לחת אבנים כראשנים “carve

you two stone tablets like the first ones (Exod 34:1).” The words

used in the narrative to describe the making of both sets also

appear in the laws of the Decalogue itself. God’s action, “making”,

is identical to that mentioned regarding the creation of the world

in the Sabbath commandment “For six days did the Lord make

the heavens and the earth, the sea and all that is in it (Exod

20:11).” The similarity between the acts of creating of the world

and the creating the first tablets led the author of the Mishnah to

include the tablets amongst the ten things created on the sixth day

just before the Sabbath.[2]

The tablets are one of God’s manifold creations. The full

significance of this point is clarified by the language God employs

in commanding Moses to make new tablets.

The root of the verb used in God’s command to

Moses, פ ס ל, has two related

meanings. As a verb it points to hewing. But as a noun it means an

“idol.” The link is clear; the type of idol is a hewn three

dimensional representation. This is how it appears in the Decalogue:

“You shall make no carved likeness (פסל)

and no image of what is in the heavens above or what is on the earth

below or what is in the waters (Exod 20:4).” The parallels between

God’s creation as noted in the Decalogue and the creation of idols

are extraordinary. Both refer to the heavens, earth and seas. An

idol is a representation of something created by God. The tablets

made by Moses are meant to represent the first tablets made by God:

“like the first ones.” God commands Moses to make tablets that

appear to fulfill the condition of proscribed images, and does so

with the very same orthography as “image.” The text which will

survive as a whole on the second tablets is, literally, carved on an

image of a divine creation created by a person. The proximity of

this act to the idolatry of the golden calf in Exodus may hint that

the act itself is inherently dangerous.

All of these details concerning the two sets of

tablets can be understood as a set of guidelines for reading the

Torah. The tablets created by God for the whole nation to see were

broken into pieces. The collective cannot grasp a text as a whole.

At the most, it can accept it bit by bit, verse by verse as it were,

but the glue that links the parts is lacking. Still, it is the whole

community, not the individual, which is entitled to receive the

original work of God’s hands. The individual is empowered to

recreate the divine creation. This is a special “dispensation” for a

dangerous act which verges on idolatry. It would appear that the

author is associating two different aspects of reading with the two

sets of tablets, analysis and synthesis.

The divine creation is given to all to

perceive, whether the heaven and the earth or the first set of

tablets. In order to understand the nature of reality and authorial

intent, it must be analyzed, broken into intelligible bits of

language. This provides for universal discourse. The Hebrew word

generally mistranslated “commandment”, דבר,

has two fundamental meanings as a noun, “thing” and “speech.” A

translation often used today in the context of the Decalogue is

“Word.” These ten Words are fundamental parts of divine speech. The

first act of reading is to understand the individual Words. As we

will see shortly, it is not at all clear how to divide the text into

ten Words. This act of analysis, shattering the divine tablets, is

the inescapable first step towards understanding the divine text.

The second step involves recreating the tablets, like Moses. One

must decide how they should be arranged. This is a dangerous step

which demands individual creativity. The application of individual

creativity makes the second tablets, the reconstruction or synthesis

“like the first”, creations. One can also become so enamored

by one’s own creation, the second tablets, that it becomes

idol-like. Nevertheless, if one is to understand the coherence of

divine creation, it must be reassembled by the individual. The Words

must be rewritten on one’s personal tablets. If the reconstruction

is successful, one will hear the voice of the author come through

the tablets, as Moses heard from the Ark of Testimony. This is the

message embedded in the narrative of the tablets, as well as the

Torah as a whole, which is demonstrated in this book.

The author seems to imply that there will

always be a personal, or subjective, aspect to a coherent reading,

one that sees the Decalogue as a composition rather than a

collection. This is the point where literary analysis can clarify

the author’s intentions. The reading presented in this section views

the Decalogue as having been composed as five consecutive pairs of

Words. As soon as the concept “pair” is introduced, we are dealing

with the individual reader’s creativity. The reader is required to

invent a concept which points to what the two members of the pair

have in common. This concept is not necessarily found in the literal

text. It is a function of the reader’s private tablets; the way the

reader perceives associations between parts of the literal,

objective, text, the ten individual Words. The reader, like Moses,

is forced to create a new set of tablets. The private tablets

contain exactly the same Words, but they are read personally.

We can summarize the author’s reading

instructions as follows. The Decalogue was constructed to be read in

two different ways. One way is suitable for public readings and

discussion. It is a “shattered” reading which reads each Word as

part of a collection of ten fundamental, but not necessarily related

Words. This reading is necessary, as the laws are part of a national

legal system which demands objectivity. The second reading is,

apparently, a function of the reader’s associative ability. It

reflects the way an individual reader perceives the Decalogue as a

composition, a work of literature composed on two stone tablets. It

is this second reading that will occupy our attention. Even though I

have emphasized the subjective aspect of this reading, it too is

based on authorial intent, as evidenced by the creation of the

second tablets by Moses at God’s command. In other words, the author

has created a document, which in order to be viewed as a

composition, demands that the reader partner with the author. The

text thus empowers the reader.

Up to now we have considered a case in which

the narrative can be read as reading instructions embedded in the

text. We will turn now to a similar yet significantly different

phenomenon. While the tablet narratives prepare the reader before

reading the Decalogue as a composition, another narrative element

verifies that the reader has grasped the way the author intended

that the Decalogue be read as a composition. We will see that

literary analysis leads to reading the ten Words as five consecutive

pairs. There is a verse that confirms this reading. Without

reference to the five-consecutive-pairs reading, the meaning of the

verse is obscure. Exodus 32:15 reads in Hebrew,

לחת כתבים משני עבריהם, מזה ומזה הם כתבים.

A literal translation would read something like “tablets written

from both their sides, from this and from that they were written.”

There are two difficulties in the Hebrew which are reflected in the

awkward English. What is meant by “from both their sides” and “from

this and from that?” It would appear that the second phrase is meant

to clarify the first and tell something about the elusive

“twofoldness” encapsulated by the two stone tablets.

The explanation of the verse, that I offer, is

an example of what I referred to as the partnership between the

author and the reader. Rather than instructing the reader how to

read the Decalogue, it serves as verification that the reader is on

the right track. In order for the verse to make sense, the reader

must first have decided that the Words can be read as five

consecutive pairs. Furthermore, it must be understood that the Words

were written alternately on one tablet and the other. Each pair has

one member of the pair on one tablet, and one on the other.

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

|

7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

10 |

Once the reader has created this visualization,

the verse makes perfect sense. The Hebrew

עבר translated “side”, must be understood in the sense of

“two sides of the street”, not “two sides of a coin.” By using the

second sense of the word, which is not common in biblical usage, the

midrash understands that the letters were carved straight

through the stone to the other side. Miraculously, letters which

were cut completely around were suspended in air. The five-pair

visualization that I propose needs no such miracle. The verse means:

“(the writing was) written across both tablets; (alternately,) on

one and (then) the other, were they written.” The tablets were

written laid out next to each other; one Word was written on one and

then its mate was written on the other. This leads to the

arrangement outlined above. While this explanation does not exist in

any of the commentaries which I have seen, it gives strong support

to the five-consecutive-pairs thesis. This is why I view it as an

instance of the author verifying a correct reading. In the course of

this book, I present the case that the whole Torah is like the text

of the Decalogue. The same word-for-word text is intended for two

different audiences. The Decalogue provides a paradigm for

identifying text constructed in this manner. The authorial hints we

have noted so far, are just the precursors for a complex system of

clues and verification embedded in the Torah.

The Divisions

As we turn now to the text of the Decalogue,

the first two steps of our investigation are dictated by our

introductory observations. First, we must decide how to divide the

text into ten Words. Second, we have to decide if there are

indications as to how they should be arranged on the two “tablets.”

If so, we must then determine why one specific arrangement should be

preferred. Only at that point will we be able to read the Ten Words

as a composition. While the presentation follows these steps, they

are actually intertwined. The division to ten is satisfying because

it leads an arrangement on the tablets which can be read as a

composition. The ultimate test of the arrangement is a combination

of the mathematical meaning of “elegance” coupled with heuristic

value. The elegance of the demonstration is determined by its

ability to tie together the laws of the Decalogue in a neat package.

The heuristic value will be displayed in later sections of the book

when we see that this solution of the Decalogue helps decipher other

textual complexities in the Torah. The following translation is

Robert Alter’s.

|

|

|

C |

J |

|

1 |

I the Lord am your God who brought you

out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slaves. |

1 |

1 |

|

2 |

You shall have no other gods beside Me. |

|

2 |

|

3 |

You shall make you no carved likeness

and no image of what is in the heavens above or what is on

the earth below or what is in the waters beneath the earth. |

|

|

|

4 |

You shall not bow down to them and |

|

|

|

5 |

you shall not worship them, for I am

the Lord your God, a jealous god, reckoning the crime of

fathers with sons, with the third generation and with the

fourth, for My foes, and doing kindness to the thousandth

generation for my friends and for those who keep My

commandments. |

|

|

|

6 |

You shall not take the name of the Lord

your God in vain, for the Lord will not acquit whosoever

takes His name in vain. |

2 |

3 |

|

7 |

Remember the Sabbath day to hallow it.

Six days you shall work and you shall do your tasks, but the

seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God. You shall do

no task, you and your son and your daughter, your male slave

or slavegirl and your beast and your sojourner who is within

your gates. For six days did the Lord make the heavens and

earth, the sea and all that is in it, and He rested on the

seventh day. Therefore did the Lord bless the Sabbath day

and hallow it. |

3 |

4 |

|

8 |

Honor your father and your mother, so

that your days may be long on the soil that the Lord your

God has given you. |

4 |

5 |

|

9 |

You shall not murder. |

5 |

6 |

|

10 |

You shall not commit adultery. |

6 |

7 |

|

11 |

You shall not steal. |

7 |

8 |

|

12 |

You shall not bear false witness

against your fellow man. |

8 |

9 |

|

13 |

You shall not covet your fellow man's

house. |

9 |

10 |

|

14 |

You shall not covet your fellow man’s

wife, or his male slave, or his slavegirl, or his ox, or his

donkey, or anything that your fellow man has. |

10 |

|

The table above shows the text of the Decalogue

divided into fourteen possible parts. The author has created a

puzzle by stating that this text contains ten divine Words. Over the

millennia, a few different solutions have been proposed. They can be

divided into two ancient “schools” on the basis of whether the two

laws that prohibit coveting, (13 and 14 above), should be considered

one or two Words. One school is Jewish and the other is Catholic.

The Catholic division derives from St. Augustine and reads them as

two Words, while Jewish sources combine them into one Word. To

offset the combination of 13 and 14, Jewish sources divide the first

word according to the Catholic division into two Words. The results

are marked in columns C(atholic) and J(ewish) in the table. There

are some differences of opinion as to whether statement 1, “I the

Lord” is part of the Decalogue. St Augustine and Philo leave it out,

while the Talmud takes as the first Word. But everyone who combines

13 and 14 in the table above has to identify two Words before 6,

“You shall not take the name.” What is clear from this is that the

author of the Torah created ambiguity by stating that there are ten

parts. The text does not number the Words, nor can it be parsed

easily. The curious reader is forced into action and must search for

clues that will lead to the author’s ten-part division.

There is one more surprising source of division

into ten, and it may be the oldest. The following illustrates how

the Decalogue is divided in Torah scrolls used in synagogues.

|

אנכי יהוה אלהיך אשר

הוצאתיך מארץ מצרים מבית עבדים לא יהיה לך אלהים אחרים על פני

לא תעשה לך פסל וכל תמונה אשר בשמים ממעל ואשר בארץ מתחת ואשר

במים מתחת לארץ לא תשתחוה להם ולא תעבדם כי אנכי יהוה אלהיך אל

קנא פקד עון אבת על בנים על שלשים ועל רבעים לשנאי ועשה חסד

לאלפים לאהבי ולשמרי מצותי

1 לא תשא את שם

יהוה אלהיך לשוא כי לא ינקה יהוה את אשר ישא את שמו לשוא

2

זכור את יום השבת

לקדשו ששת ימים תעבד ועשית כל מלאכתך ויום השביעי שבת ליהוה

אלהיך לא תעשה כל מלאכה אתה ובנך ובתך עבדך ואמתך ובהמתך וגרך

אשר בשעריך כי ששת ימים עשה יהוה את השמים ואת הארץ את הים ואת

כל אשר בם וינח ביום השביעי על כן ברך יהוה את יום השבת

ויקדשהו 3

כבד את אביך ואת אמך למען יארכון ימיך על האדמה אשר

יהוה אלהיך נתן לך 4

לא תרצח 5

לא תנאף 6

לא תגנב 7

לא תענה ברעך עד שקר

8 לא תחמד בית

רעך 9

לא תחמד אשת רעך ועבדו ואמתו ושורו וחמרו וכל אשר לרעך

10 |

The text of the Torah is divided into

paragraph-like divisions throughout the scroll. There are two kinds

of divisions, major and minor. The illustration shows exactly how

the Decalogue looks in the scrolls except for the addition of

numerals I have placed after each Word. The division is like the

Catholic division, with an additional flourish; there is a major

break before the third Word, “Remember the Sabbath.” There is a

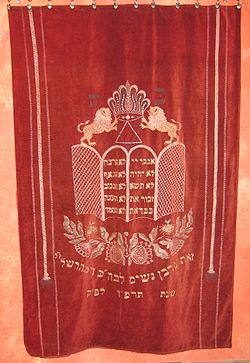

great irony connected with the scroll division. In many synagogues,

the ark in which the Torah is placed is covered by a curtain

embellished with a representation of the tablets of the Decalogue.

Invariably, the division depicted on the curtain, as below, is the

“Jewish” division in the table above. That means that the curtain

shows a different division than the one contained in the Torah

scroll behind the veil.

So we have one division accepted by Jewish

commentators at least since the time of Philo, and another, in the

Torah scroll, totally ignored. In order to understand just how

strange this phenomenon is, it is necessary to know how sacrosanct

the written form of the Torah scroll is. If just one letter or one

division is incorrect, the scroll cannot be used for public reading.

“Paragraph” spacing is ancient, appearing in Dead Sea scrolls, and

is discussed in rabbinic literature. It could well be that St.

Augustine based his division on the scroll division. Why then has

Jewish tradition totally ignored the evidence of the Torah scroll?

This is a mystery. I propose a solution to this mystery in Part 5.

The following is the arrangement of the Words in consecutive pairs

according to the scroll divisions.

Five Pairs of Words According to the Scroll

|

אA I the Lord am your God who brought you

out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slaves. You

shall have no other gods beside Me. You shall make you no

carved likeness and no image of what is in the heavens above

or what is on the earth below or what is in the waters

beneath the earth. You shall not bow down to them and you

shall not worship them, for I am the Lord your God, a

jealous god, reckoning the crime of fathers with sons, with

the third generation and with the fourth, for My foes, and

doing kindness to the thousandth generation for my friends

and for those who keep My commandments. |

בA You shall not take the name of the Lord

your God in vain, for the Lord will not acquit whosoever

takes His name in vain. |

|

אB Remember the Sabbath day to hallow it.

Six days you shall work and you shall do your tasks, but the

seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God. You shall do

no task, you and your son and your daughter, your male slave

or slavegirl and your beast and your sojourner who is within

your gates. For six days did the Lord make the heavens and

earth, the sea and all that is in it, and He rested on the

seventh day. Therefore did the Lord bless the Sabbath day

and hallow it. |

בB Honor your father and your mother, so

that your days may be long on the soil that the Lord your

God has given you. |

|

אC You shall not murder. |

בC You shall not commit adultery. |

|

אD You shall not steal. |

בD You shall not bear false witness

against your fellow man. |

|

אE You shall not covet your fellow man's

house. |

בE You shall not covet your fellow man’s

wife, or his male slave, or his slavegirl, or his ox, or his

donkey, or anything that your fellow man has. |

Defining the Five Pairs

I have arranged the Words in consecutive pairs

(A-E) above. The first Word in each pair is marked

א, and the second

ב. This arrangement leads to the

identification of five subject categories for the five pairs. This

is the first step of the process of reading the whole tablets. The

appearance of five subjects for the five pairs is an indication that

we are beginning to hear a voice which has waited silently here in

the Torah for some time. The more certain that we can be about the

significance of the five subjects, the more clearly we are hearing

the voice of the author. Most of the remainder of this section will

be devoted to demonstrating how carefully the five pairs have been

constructed, as well as some of the new avenues of interpretation

that a reading according to the structure opens.

I am also delaying the presentation of my five subjects so that you

can go back and try for yourself. See whether you think that the

five pairs represent five, possibly related, ideas. You can then use

my reading to improve your own, or vice-versa. This is a crucial

point for following my method in this book. I present a tool found

within the Torah which enables readers to develop creative readings.

My interpretations are not to be given any special weight. They are

presented as an example of how one person tries to use a structural

reading in order to probe the inner unity of the text. Now I will

explain how I identify these five pairs of Words.

The last two Words are clearly a pair,

beginning with the same words: "You shall not covet." The

self-defined common theme is coveting. Also at the beginning of the

list we can see a clear pair of Words. Both "I the Lord" and "You

shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain" refer directly

to the Lord. This pair of Words is setoff according to the scroll

paragraphing, as we saw above, by a major division. This is the only

major division in the Decalogue and immediately signals an intended

arrangement as pairs. (In contrast, according to the alternative

ways of dividing up the Decalogue, this line break comes after the

3rd Word, where it is not particularly meaningful.)

[3] The third and fourth Words

are a structural pair and are similar in several ways:

·

They differ from all the other Words in that they

are imperatives, "Remember" and "Honor", while the other eight Words

are injunctions.

·

Both imperatives include a temporal component "six

days", "that your days may be long."

·

They both state reasons for observing the Words and

refer to the Lord in these reasons: "For six days did the Lord make

the heavens and earth", "that your days may be long on the soil that

the Lord your God has given you." The two reasons have an

interesting relationship to each other. The first is historical

referring to the creation of the world. The second reason is also

within the framework of time, but opposite in direction from the

first, pointing to the future rather than the past: enjoying a long

life in the future.

There are enough similarities between the third

and fourth Words to warrant considering them a pair. Yet, lest there

be the slightest doubt as to whether these two Words are a pair, the

Torah has Moses drive the point home with the retelling of the ten

Words in Deuteronomy 5. There he adds the identical addition to both

Words: "as the Lord your God commanded you" (vs. 15-16). This common

addition to the third and fourth Words removes any doubt that we are

to read these two as a pair. It also points to the common thread,

God’s involvement with human life. Having now identified the first

four and last two Words as three pairs, we are left with four simple

injunctions:

אC. You shall

not murder.

בC. You shall

not commit adultery.

אD. You shall

not steal.

בD. You shall

not bear false witness against your fellow man.

All four Words refer to social offenses,

connections between one person and another, or taking something from

another. The first two, murder and adultery, (אC

and בC), which are both capital

crimes in the Torah, have a bodily component lacking in the next

two. They also point to the beginning and end of the life cycle:

propagation and death, thereby defining the common subject, human

life. The remaining pair, D, includes two ways of depriving someone

of what belongs to her or him, be it property or reputation. A brief

look at the Words in pairs has yielded the following five

provisional subjects:

A.

God

B.

God and time

C.

The extent of human life

D.

Possessions (property and reputation)

E.

Coveting

In the course of the following analysis we can

expect to modify some of these definitions.

The Arrangement on the Stone Tablets

Before considering the conceptual pattern

created by the five common subjects, I want to anchor the five-pair

arrangement in the biblical narrative. This arrangement leads to a

new visualization of what might have been the format of the writing

on the two stone tablets. If we take the two columns of our table to

represent the two stone tablets, then one tablet (א)

contains the first Word of each pair and the other tablet (ב)

contains the second Word of each pair. Admittedly, this arrangement

goes up against all traditional visualizations, which apply a linear

block of Words to each tablet, such as the arrangement on the ark

cover pictured above with the first five Words on one tablet, and

the last five on the other tablet. Despite the lack of references to

our arrangement in classical commentaries, the Torah itself, in

Exodus 32:15, may describe the proposed arrangement. This is the

verse noted earlier as verification. Our tablets are written as two

parallel columns. Each tablet is a column. The writing goes across

both columns (tablets), from one to the other, alternately. This is

clearly the gist of the verse which now justifies the division

according to the scroll and the consequent arrangement in

consecutive pairs.

What Difference Does It Make?

At this point, a critical reader might well ask

“What difference does it make how we arrange the Words, since their

content does not change?” There are two answers to this question.

First, by arranging the Words correctly we recreate the structure

that defines the context of each Word. Whatever knowledge can be

derived from context requires an understanding of structure. Each

stone tablet is a context for the five Words written on it. We are

now in a position to read each tablet as a coherent set. Second, and

to my mind more important and more exciting, identifying the

structure enables the reader to view the whole as a composition.

This view leads to understanding the organizing principles that

underlie the choice of these ten Words to create the Decalogue. If

we are right about reading the Words in pairs, then we have a means

of discovering new information that was not available before we

grouped the Words in pairs. For example, each pair must have a

common subject which defines it as a pair. That gives us five new

ideas, the subjects of the pairs, which were inaccessible without

first identifying the structure. We are beginning to read a text,

the existence of which I suggested was hinted at by the narratives

of the two sets of tablets. It is a text written between the lines,

hidden right in front of our eyes. We can now begin reading the

composition composed by means of the five pairs.

Hierarchical Organization of the

Pairs

The first evidence, that the five-pair

arrangement might lead us to the literary/conceptual plan of the

Decalogue, is the hierarchical organization of the five subjects we

identified. There is a flow from pair to pair that leads from God

and His name in pair A to coveting, an expression of human

subjectivity, in pair E. The intermediate pairs demonstrate that

there is a graduated passage from the most encompassing of all

possible subjects, God, to the most limited, one that may be no more

than a chimera, a private human emotion. Pair B is firmly linked to

God because it contains references to Him in the reasons it presents

for observing the Sabbath and honoring parents. Unlike pair A,

however, the subject of pair B is not God or His name, but rather

the manner in which He affects His creatures through the medium of

time. God does not appear in pair C, which focuses on human life.

There may be an implied link to the time theme of pair B, because

pair C encompasses the human lifespan from propagation to death.

Pair B deals with time on a divine scale, from the creation of the

world to some uncharted future in the Promised Land. In any case,

the disappearance of God in pair C places it after pair B in the

hierarchy. Pair D, dealing only with property and reputation, is

lower in the hierarchy than C which deals with life itself. Finally,

pair E has no real identifiable content that transcends pure

subjectivity. The hierarchical organization of the pairs is strong

evidence that we are beginning to hear the voice of the author.

The Symmetry of the Pairs

Now that we have determined that the five pairs

are ordered hierarchically, we will turn to another formal literary

device that can be identified in the order of the pairs:

symmetry. Several different symmetries can be seen in the

structure. The first symmetry can be discerned from the fact that

the middle element, pair C, divides the five-pair structure of the

Decalogue symmetrically: pairs A and B are connected to God; pairs D

and E are connected with property and reputation. It is possible to

interpret this symmetry in light of the hierarchical organization.

For example, we might say that the structure indicates that human

life (pair C) has both an “upper” divine aspect (pairs A, B) as well

as a “lower” mundane aspect (pairs D, E). While this observation may

be valuable in and of itself, the structure contains two more

symmetries which will lead us to even more intriguing observations.

The extremities, pairs A and E, share a

similarity, as do the adjacent pairs, B and D. The similarity

between God, as He appears in A, and the aspect of people addressed

in E is that both describe emotive beings. God describes Himself as

“a jealous god” (A) while people are commanded to restrain their

passions “you shall not covet (E).” The

appearance of emotions in the extreme pairs may indicate that the

theme of pair E is more than “coveting.” It seems that the structure

is directing us to compare God Himself (A) with individual human

personality or subjectivity (E). The symmetry of pairs B and D will

enable us to better understand the implied connection between A and

E.

The similarity between pairs B and D is a

function of the connection between each of them and the adjacent

extreme pair (A and E). It is not difficult to see a connection

between coveting (E) and dishonesty (D). The latter may well be the

result of the former. In other words, pair D appears to stand in a

relationship with pair E which is the opposite of the order of the

pairs, if we see D as a result of E. In general terms, we can say

that the actions mentioned in pair D are an expression of desire or

will, the subject of E: the subjective individual of E expresses

elements of that subjectivity by means of the actions in D. We can

see the same relationship between pairs A and B. Pair B contains

positive actions demanded by God, the subject of A. Observing the

Sabbath and honoring parents are concrete expressions of divine

will. We will now integrate the symmetries.

The extremities of the five-pair structure

point to two unique spiritual entities: God (A) and the subjective

individual, the “I” or self (E). Between them are three separate

realms of experience: pairs B-D. One is closer to the divine, (B),

and describes actions that are a function of divine will (A). The

other is closer to the self, (D) and describes actions that are

functions of human will (E). The middle pair (C) thus represents the

meeting point of God and the self. This view reinforces our original

observation that pair C indicates “human life” from conception to

death. The physical existence of the person combines actions that

are determined by the free-will, with processes, such as birth and

aging, which are beyond the individual’s control. The following

table summarizes the symmetries of the pairs.

|

Pair |

Subject of Pair |

|

A |

God |

|

B |

Actions based on divine will |

|

C |

Physical human life |

|

D |

Actions based on human will |

|

E |

Subjective human will |

It could be argued at this point that we are

engaging in highly speculative homiletics rather than textual

analysis. This appearance is unavoidable considering the type of

interpretation that we are being led to by the text. Once we have

concluded that the text is based on pairs of Words, we begin dealing

with what is written “between the lines”, the unwritten common

themes of the pairs. Defining the common themes is a synthetic

interpretive act, justified by the fact that the text was

constructed in pairs. The interpretation should be judged on its

ability to integrate the diverse parts of the structure, without

forcing it. If possible, it is desirable to find further evidence to

support the hypothetical reading. In the case of the symmetry of the

pairs, we can find supporting evidence in the internal symmetries of

two individual Words, Aא and Bא.

We will see that these two Words share important structural patterns

with the five-pair structure, based on “conceptual symmetry”. (This

is a phenomenon that we shall encounter throughout the Torah.) We

will begin by examining אB because

it captures the exact pattern we have just seen in the five-pair

structure, although the order is reversed, beginning with people and

ending with God.

The Structure of the Third Word (אB)

|

a. Human holiness |

Remember the Sabbath day to hallow

it |

|||||||

|

b. Human labor |

|

Six days you shall work and you

shall do your tasks but the seventh day is a sabbath to

the Lord your God. |

|

|

||||

|

c. The interface between |

I |

|

You shall do no task, you |

|

|

|

||

|

II |

|

|

your son or daughter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

III |

|

|

your male slave or slavegirl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

IV |

|

|

your beast, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

|

and your sojourner who is within

your gates |

|

|

|

|||

|

d. Divine labor |

|

For six days did the Lord make the

heavens and earth, the sea and all that is in it, and He

rested on the seventh day. |

|

|

||||

|

e. Divine holiness |

Therefore did the Lord bless the

Sabbath day and hallow it. |

|||||||

The above chart demonstrates two levels of

structure within אB, one that

divides it into five elements (a-e) and one that divides element c

into five parts (I-V). The central element (c) divides the Word

symmetrically between divine and human actions, much like pair C in

the larger structure. The Word opens with human sanctification of

the Sabbath (a) and closes with the divine parallel (e). The

relationship between these clauses is similar to the relationship

that we found between pairs A and E, which we described as focused

on the divine and the human subjectivity, although in reverse order.

The relationship between clauses (b) and (d) is virtually identical

to that which we found between pairs B and D: human labor is

parallel to “actions that are a function of human will”, and divine

labor is parallel to “actions that are a function of divine will.”

Here too, the framework around the central element creates a

conceptual pattern that prepares the reader to see the middle as a

meeting point between the human and the divine.

Order within the Central Element of the Third Word

|

I |

You shall do no task, you |

Self |

|

II |

your son and your daughter, |

Dependent offspring |

|

III |

your male slave or slavegirl |

Dependent slaves |

|

IV |

And your beast, |

Dependent livestock |

|

V |

and your sojourner who is within

your gates. |

Dependent, outside household |

The Meeting Point between God and the Individual

There are two distinct ways to explore the

significance of the central element as a link between the human and

the divine. In the manner of traditional homiletics, we could note

that people take responsibility for other creatures in (c). They are

referred to in element (d) as God’s creatures, "the Lord made the

heavens and earth, the sea and all that is in it." From this point

of view, the connection between the human and the divine involves

human responsibility for the divine creation. While this conclusion

is certainly true, it does not take into account the full depth of

the text. In order to do so, it is necessary to relate to the

ordered elements of (c). The central element, III, refers to a

master/servant relationship. This is the focal point. The separate

realms of the divine (d, e) and the human (a, b) meet at the element

focused on the master/servant relationship, (c). Word

אB focuses on the way the

relationship between God and the individual is projected onto the

individual’s relationship with dependents. The individual’s

relationship with God is ultimately tested by the way the individual

treats those who are dependent on him/her for their well-being.

It is noteworthy that the five-part

אB, as well as its five part third

element within it (c), are both organized from the close to the

distant. The details of c are especially relevant for the light they

shine on the full Decalogue structure. The order of the five parts

of c establishes a progression from (I) the self, through (II)

offspring, (III) dependent slaves, (IV) dependent livestock, and

finally (V) the dependent outside the household (גר).

In the broader framework of אB,

this progression takes the form of movement from self to God. By

observing this principle of organization within one of the Words, we

have justified our identification of this order in the full

five-pair structure of the Decalogue. It would seem that Word

אB is an inverted fractal of the

five-pair structure, in terms of the “divine/human” organizing

principle. We will now look at the five-part structure of Word

אA which is directly parallel to

the five-Word structure.

The Five Parts of the First Word

|

a. God’s action in political

history |

I am the Lord your God who brought

you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of

slaves. |

|||

|

Forbidden human

actions |

b. Other gods |

|

You shall have no other gods beside

Me. |

|

|

|

c. Images |

|

You shall make you no carved

likeness and no image of what is in heavens above, or what is on the earth below, or what is in the waters beneath

the earth; |

|

|

d. Worship of other gods |

|

you shall not bow down to them, and

you shall not worship them; |

||

|

e. God’s reaction to acts of

individuals |

for I am the Lord your God, a

jealous god, reckoning the crime of fathers with sons,

with the third generation and with the fourth, for My

foes (those who hate Me), and doing kindness to the

thousandth generation for my friends (those who love me)

and for those who keep My commandments. |

|||

We have now examined two five-part structures,

the pairs of Words and Word אB and

seen that have some common features. Since Word

אA also has a five-part structure,

we can examine its structure in light of the other two. We will see

that all three share elements of structure as well as content. The

points noted in the previous five-part structures which will be

compared to אA are symmetry,

hierarchical organization, and the relationship between humans and

the divinity. The first symmetry in אA

is that which is formed by the first (a) and last (e) elements to

create a framework. They both relate divine acts and contain “I am

YHWH your God.” They differ in that they contain two different

aspects of YHWH, national and personal. In “a” we see Him acting in

history without mention of any cause. In “e” He speaks of rewards

and punishments for individuals. He refers both to His emotion,

“jealous”, as well as human emotions, “hate” and “love.” This

pairing immediately reminds us of pairs A and E of the macro

structure which we identified with divine will (A), like

אAa, and human will (E), like

אAe. The symmetry of

אAa and אAe

is emphasized by them being first person statements, as opposed to

the central elements, אAb-d, which

are second person prohibitions.

The integration of the five parts of

אA, like the pairs of Words and

אB, is accomplished by linking

together the first two parts, “a” and “b”, and the last two “d” and

“e”. A clear distinction between the first two and the last two is

that “a” and “b” have no mention of human influence on God or gods,

while “d” and “e” do. In “d” are references to worship, attempts to

influence the gods. In “e”, God tells how He is affected by human

emotions of love and hate; people influence God. The last

observation raises the possibility that the process described by the

five parts of אA involves a

transition from God’s influence on people on the national level in

“a” to individuals’ influences on God in “e”. If so, what then is

the place of “gods” and images?

The three central elements, unlike the

framework, are all injunctions. If the five-part structure of

אA follows the “rules” we have

noted in the five pairs as well as in אB,

we can make some predictions. First, elements b and d will have a

connection that solidifies the symmetry around c. Second, element c

will be the fulcrum or meeting point between one concept which

combines a and b and another which combines d and e. Third, a

hierarchy or flow will link all five elements. We will begin with

the symmetry of b and d. There is a textual problem regarding these

elements which has been the source of disagreement between exegetes.

The problem is based on the question of whether element c is

actually connected to b and d or not. Some read c as “a

comprehensive prohibition of image-making” (Alter 429) and thus not

linked to the surrounding prohibitions, while others read it as

specifically referring to cultic icons and therefor linked. Close

grammatical analysis supports that “d” refers back to “b”: “You

shall have no other gods (b)… and you shall not bow down to them

(d).” This reading is supported by the structures of the pairs as

well as אB, in which the central

element is the focus of the other four symmetrically arranged

elements. We can test this hypothesis regarding

אA by determining whether “c” is a

fulcrum and whether the five parts create a hierarchy or flow.

The author has constructed “c” so that it

contains a visual hierarchy within it which also links it to

אB: heaven above, the earth, water

below, “For six days did the Lord make the heavens and earth, the

sea.” The link to Word אB leads

back to the days of creation. We will see in Part 2 that the visual

hierarchy is found in the days of creation when they are divided

into two cycles of three days each. Days one and four are “above”,

two and five are “in the middle”, and three and six “below.” This

three-tiered image will play a significant role in the analysis of

other structures in the Torah, including the book of Leviticus in

Part 4. The visual hierarchy in אA

provides an aid to understanding the link between the three

injunctions and places them within the framework.

“You shall not bow down to them” in “d” refers

to downward motion and so connects with the “below” aspect of the

visual key. That would imply that “You shall have no other gods

beside Me” (b) is connected to the “above” aspect. As the “gods”

referred to in “b” are not idols, it is likely that they are the

heavenly “hosts”, sun, moon, planets, stars, constellations; all the

heavenly powers thought to have influence on the earth. As such,

they are “above.” According to this reading, “c” integrates “above”

from “b”, and “below” from “d” with the middle, the earth, which is

unique to “c”. In this manner the three middle injunctions (b-d)

create a transition from an aspect of God which the author places

above, the mover of nations, and an aspect which is below, a

personal God who responds to the actions of individuals. We were

able to see this flow because of two similar five-part structures:

Word אB and the

five-consecutive-pair arrangement of the ten Words.

The Distinction between the Tablets: Divine Dyads

Now we will turn to another bit of information

offered by the Torah that may broaden our understanding of the

Decalogue: the Words were written on two stone tablets. What is the

significance of the two stone tablets? Those who divided the Words

like Philo and the rabbis found that their division offered a

conceptually satisfying distinction between the first five Words and

the next. They considered that this division reflected God’s reason

for dividing the Words between two tablets. The first five Words,

according to their division, all mention God, while the last five do

not. Consequently, they placed the first five on one tablet and the

next five on the second. One tablet was considered to contain laws

between people and God, while the other contained laws between

people and people. Apparently, this division was so satisfying that

they were willing to ignore the way it corrupted the literary

coherence of the first Word according to the scroll, as well as the

text’s insistence that there be two separate injunctions against

coveting. Even though we have found strong evidence that the scroll

division arranged in pairs reflects a coherent literary plan, we

must still explain why the Words were written on two separate

tablets. What additional meaning could this impart?

The arrangement of the Words in five pairs,

leads to seeing them arranged on the tablets in such a way that the

first of each pair is on one tablet and the second is on the other.

This is the way we explained Ex. 32:15, the Words were written

“across” from each other. So we now have two separate groups of

Words on the two tablets, א (1, 3,

5, 7, 9) and ב (2, 4, 6, 8, 10).

The fact that they are divided between the tablets would seem to

indicate that we should find a meaningful distinction between groups

א and ב.

Furthermore, the distinction should be fundamental enough to justify

the divine act of creating two tablets. In other words, we are

searching for a “divine dyad”, one of such fundamental importance

that it was embodied in the two stone tablets which God created to

give to Moses.

In order to clarify the concept of “divine

dyad”, as well to gather evidence that might shed light on the stone

tablets, we will examine several other “divine dyads”, pairs

connected with divine creation. One of them is obviously a pair, the

two special trees in the Garden of Eden. Another pair is the two

Adams of Genesis 1 and 2. A different dyad connected with the

creation is less obvious. It is based on dividing

the six days of creation into two three-day cycles. Finally, we will

consider one more pair associated with the Decalogue, the two

different sets of stone tablets. We will see that all these “divine

dyads” share a common characteristic vis-à-vis their “twofoldness”.

After examining these additional dyads, we will see that their

common characteristic applies to the tablets of the Decalogue as

well.

One and Many in the Creation

It is well known that the six days of creation

form three pairs: days one and four speak of light, days two and

five the sky and water and what lives in them, days three and six

the earth and what lives on it. What is less well known is that

there is a fixed relationship between the first three days and their

parallels in days four to six. On the first three days God creates

and names individual entities, light, sky and earth. Each of the

three is defined by separation. God separates light from darkness;

the sky separates above from below; and the earth is revealed by the

separation of the water into oceans. On the next three days God

creates classes of objects and does not name them: heavenly lights

on day four, birds and fish on day five, terrestrial animals and

people on day six. In contrast to the “separated” creations of days

1-3, the creations of days 4-6 are all “connected”. On days 5 and 6

the creations are told to be fruitful and multiply. On day 4 the

lights “rule” and serve as “signs”. So the six days can be read as

two cycles, 1-3 and 4-6, distinguished by principles of “one and

many” and “separated and connected”. The fact that God created the

world in a manner that incorporates or exemplifies these dyads

implies that they are to be considered principles of divine

metaphysics. Perhaps even more significantly, it testifies that

philosophical and metaphysical principles are embedded in the

structure of the biblical narrative. This is the type of knowledge

that would justify the creation of two stone tablets. We will return

to the creation narrative in Part 2.

The Guarding Cherubim

Another dyad rooted in the creation story will

shed further light on this investigation, the Tree of Life and the

Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad. The Torah connects the two stone

tablets with the two named trees in the Garden of Eden. The

connection is made by means of the appearance of Cherubim in

association with both the tablets and the trees. The function of the

Cherubim in both cases is similar. Regarding the tablets, the

Cherubim were attached to the cover of the Ark containing the

tablets. They are described with their wings spread out as

סוככים (covering) the Ark. While

the Hebrew is usually understood as “cover”, it can also have the

sense of “protect.” The Cherubim were placed outside of the Garden

of Eden in order לשמור (to

protect). In addition, God is present in the Holy of Holies where He

speaks with Moses. Similarly, God is present in the Garden of Eden

where Adam hears His voice “מתהלך”

(walking about). So the parallel presence of the Cherubim, combined

with the similarity of their functions and the presence of God’s

voice, suggests that we look for a parallel between the two tablets

of stone, and the two trees.

The Trees

The function of the Tree of Life is,

apparently, to maintain the life of the person who eats from it. The

effect is limited to the eater and is essentially invisible to an

observer. The effects of eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good

and Bad can be observed from the change that took place in Adam and

Eve. The Torah tells us that before eating from the Tree they were

naked, but they were not ashamed. After eating they were ashamed and

covered themselves with fig leaves. Shame, as opposed to life - from

the Tree of Life, requires the presence of another person. The text

is very specific to use a plural reflexive form of the verb

translated “were not ashamed”, indicating that it is a social

emotion, one requiring a common set of values. These common values

were received by eating the forbidden fruit. Therefore, one of the

differences between the two trees is that the Tree of Life has a

purely personal, existential, effect, while the Tree of Knowledge of

Good and Bad has a social, or relational, effect. Moreover, the name

of the Tree of Knowledge is formulated in a manner that implies the

use of language. “Good and Bad” are linguistic attributes. Therefore

the Tree of Knowledge presupposes the use of language, which is not

true of the Tree of Life. Speech, being an act of social intercourse

requires an “other”. So we have yet another indication that the Tree

of Knowledge is in some way “social” while the Tree of Life is

personal. There is a similarity between this distinction between the

trees and the distinction we saw between the two three-day cycles in

the creation. The first cycle, days 1-3, like the Tree of Life,

concerns individual entities, while the second cycle, days 4-6, like

the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad concerns connected group

entities. We will see that the conceptual similarity between dyadic

elements of God’s creation in the early chapters of Genesis extends

to His creation in Exodus, the stone tablets: the primal dyads of

“one and many” “separate and connected” are embodied by the two

tablets. Tablet א focuses on the

individual, and tablet ב focuses on

social interactions.

Two Adams: Humankind and “the Man”

The name “Adam” is used in both creation

narratives. However, in the second narrative in Gen 2, it appears

invariably with the definite article “ה”

(the), consequently I shall refer to him as “the Man.” He is created

as a singular individual from the dust of the earth and the divine

life force in Genesis 2:7: “Then the LORD God formed the Man of the

dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of

life; and the Man became a living soul.” Adam of the first chapter

appears without the definite article in Genesis 1:26 “And God said:

‘Let us make Adam in our image, after our likeness; and let them

have dominion….” I will refer to Adam of the

first chapter as “Humankind”. Humankind were created male and female

and together given the collective name “Adam.” So the two creation

narratives introduce us to another divine dyad based on the

distinction between one and many, singular and connected. The Man of

ch. 2 is singular and so unconnected that God Himself observes that

“It is not good that the Man should be alone; I will make him a

sustainer beside him (Genesis 2:18).” Humankind in ch. 1 are created

in the image and likeness of an aspect of the divinity which itself

is expressed in a plural form, “in our image, after our likeness.”

From here, it would appear that the dyad of “one and many” is so

fundamental that it in some way touches the very identity of God.

The last dyad is the two sets of stone tablets. We have already seen

that the dyad “one and many” applies to them; the first tablets for

the many and the second for Moses. We have now examined four

examples of the divine dyad “one and many”; one regarding the two

sets of tablets, and three from creation narratives: the two cycles

of days, the Edenic trees and the two Adams. We will now see that

this dyad is also associated with the two sets of Words we have

identified with two tablets, א and

ב.

Identifying the Trees with the Tablets

The names given to the two trees in the Garden

are closely associated with the central pair of Words,

אC and בC.

Word אC prohibits killing and is

thus an obvious link to the Tree of Life. In order to see the

connection between בC, “Do not

commit adultery”, and the Tree of Knowledge, it is only necessary to

note that the Hebrew word for “knowledge” is identical to the word

for carnal knowledge, as in “Adam knew Eve.” So the central

pair of words virtually labels the tablets for us with their

parallel Edenic trees. We have already seen that these trees reflect

the divine dyad “one and many”, so the association of each tree with

the central Word of one of the tablets may indicate that the

distinction between one and many is the divine dyad we are searching

for. If so, tablet א, linked to the

tree of life, would embody the principle “one” or “separate” and

tablet ב the principle of “many” or

“connected”.

The Objects of Pair E

Pair E provides us with another piece of

evidence to apply to our comparison of the tablets. Both Words

prohibit the same action, coveting. This enabled us to easily point

to the common subject of the pair. Since the verbs are identical,

the distinction between the Words must be found in the objects of

the verb. Word אE contains a single

object, a house. Word בE, on the

other hand, contains multiple objects, “your fellow man’s wife, or

his male or female slave, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that

is your fellow man’s.” The distinction between a single object and

multiple objects is maintained in the version of the Decalogue in

Deuteronomy. There, although the two Words in Deuteronomy have

different verbs and different objects than in Ex., the Word parallel

to אE has a single object while the

Word parallel to בE has multiple

objects. It would appear then, that the distinction between

אE and בE,

one and many, is consistent with the hint we gathered from the

connection with the Edenic trees, and that the divine dyad

underlying the creation of two tablets is indeed related to the dyad

of the six days of creation, “one and many”, with tablet

א expressing “one” and tablet

ב “many”.

The Dyad of “Separate and Connected”

Our third observation is that there is a

plethora of interpersonal relationships mentioned on tablet

ב which are lacking on tablet

א. Words

בB, בC, and

בE all refer, whether directly or

indirectly, to marriage, while no Word on

א does. Although בD does not

refer to marriage, it does refer to an act that requires two people,

witnessing: “One witness shall not rise up against a man for any

iniquity, or for any sin, in any sin that he sinneth; at the mouth

of two witnesses, or at the mouth of three witnesses, shall a matter

be established” (Deut 19:15). Similarly, בA

refers to taking an oath, an act carried out in a court. None of the

laws on tablet א deal with these

types of relationships. To clarify this point, we can take the

example of pair D. “You shall not steal” (אD)

has a thief and a victim, but no implied connection between them

other than the crime itself. “You shall not bear false witness

against your fellow man” (בD), as

we have noted, implies collusion between two or more lying witnesses

who testify against their “fellow man.” So there are additional

social components in the laws of tablet ב.

This last point indicates a link with the dyad of the two three-day

cycles of creation that is more than simply “one and many”. We also

saw that the first three-day cycle is characterized by separation

while the second cycle is characterized by connections, such as “be

fruitful and multiply.” So the dyad “separate – connected”, as in

“the Man - Humankind” is also embodied in the tablets. This

completes our investigation of divine dyads and their application to

the two stone tablets.

The Decalogue is a True Table

We have now found two different types of

organization in the two tablets of the Decalogue. They can be

described as “horizontal and vertical.” By “horizontal”, I mean the

division into the five hierarchically ordered pairs. The vertical

organization was highlighted by God arranging the Words on two

tablets according to the divine dyad. The cumulative effect of the

two different organizing principles is to identify the two tablet

format as a true table. Each individual law is a function of two

organizing principles, the subject of its pair (row) and the subject

of its tablet (column). The tablets can be considered a type of

Cartesian coordinate system representing “conceptual space”. Each

point (Word) in the plane has a conceptual value defined by the

intersection of two concepts, the horizontal and the vertical. In

conclusion, it would appear that the Decalogue was conceived and

constructed as a two dimensional text, a table or weave. In the

Decalogue, the pairs can be viewed as weft threads and the tablets

as warp threads. All of the Torah is composed of woven text. The

stone tablets, engraved by God, are the paradigm. We will see in the

next section that the creation is also a weave.